With that in mind, I accepted Talens’ challenge. They asked me to work with a very limited palette and then finish with glazes using surprise colours I would not know until the base was completed. This is not my usual way of painting, as I normally work directly, alla prima, but that was precisely why it was worth doing. Sometimes, to learn, you have to allow the painting to contradict you, pulling you away from comfortable gestures and reminding you that what matters is not control but looking more deeply.

Starting with a limited palette

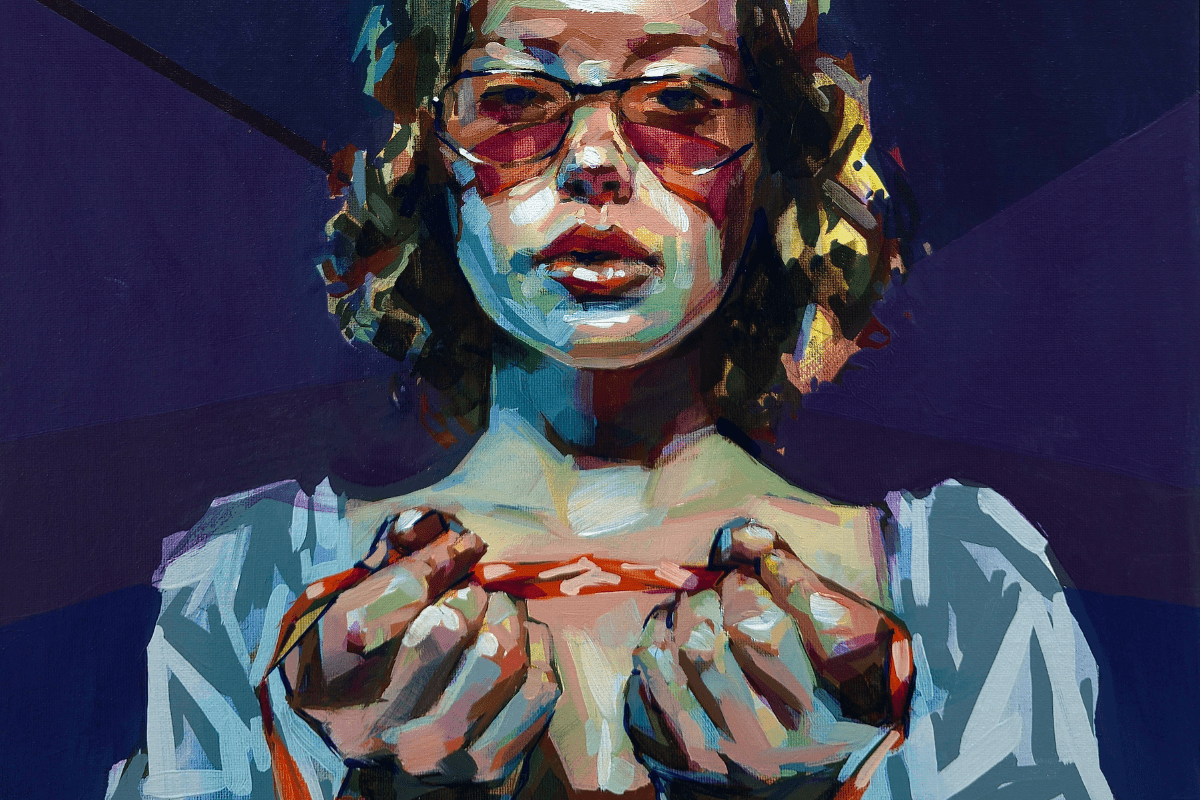

To sustain the experiment, I relied on a method I developed at university and continue to use in my workshops: a chromatic grisaille in four ranges. Working from dark to light, I divide the painting into darks, dark midtones, light midtones and lights. Each range is considered in two temperatures, cool and warm, to keep the palette vibrant. I am not aiming for exact chromatic fidelity to the subject; I am building a structure of value and temperature to understand forms and create volume. This solid, flexible base allows me to take risks with glazes later.

The drawing comes first, and there are many ways to approach it: freehand, with a projector, transfer paper or a grid. I usually transfer it with graphite on the back of a photocopy, then press it onto the canvas. This marks the main limits, after which I finish the drawing freehand. Understanding forms is essential; a mechanical trace is useless if you do not know how to draw.

On top of the drawing, I apply a chromatic imprimatura: a very diluted wash of pure colour without white, almost like a veil. It does not darken the canvas but adds energy and softens the rigidity of the white. I apply it with a soft bristle flat brush loaded with turpentine, sweeping across the surface. Letting it dry slightly helps the following layers adhere better.